Wilder Research Helps St. Louis Park Understand and Find Solutions to Food Insecurity

Food insecurity—not having reliable and sufficient amounts of affordable, nutritious food—may be an unfamiliar term, but the problem is not new. Food insecurity is tied to poverty, but is also impacted by transportation, low wages, housing and health care costs, and access to grocery stores. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity had been declining since the recession, but food shelf use continued to rise, with Minnesotans visiting food shelves 3.4 million times in 2017.

In 2018, local advocates asked the City of St. Louis Park to do more to address food insecurity in their community. In 2019, the city hired Wilder Research to conduct a citywide study to identify current resources, barriers, and opportunities. The data would be used to guide action to help ensure everyone in the community has access to nutritious, affordable food.

An estimated 1 in 8 Minnesotans experience food insecurity, up from 1 in 11 pre-COVID.

Second Harvest HeartlandWho Is Most Impacted by Food Insecurity in St. Louis Park?

The 2018 Hennepin County SHAPE Survey found that 12% of residents in St. Louis Park and Hopkins “sometimes” or “often” worry that they will run out of food before having money to buy more. Wilder Research identified specific populations in St. Louis Park who may be at greater risk of food insecurity, including children:

- Children: 30% of St. Louis Park ninth grade students received free or reduce priced lunches available for students living in low-income households. 6% reported missing one or more meals because their family didn’t have enough money to buy food.

- Older adults: 8% of St. Louis Park residents 65 years or older live below the federal poverty line. 35% of older adults have a disability, which could impact mobility and food access.

- Households living near or below the poverty line: 18% of St. Louis Park residents have an annual household income below 200% of the federal poverty level, an estimate of financial instability and threshold used for some public benefit programs.

- Immigrant communities: A food shelf representative noted 26% of those they serve identified as Latino, and the number of African, Russian and other Eastern European immigrants they serve is a growing.

“Food insecurity can be invisible in some communities,” said Amanda Hane, Wilder Research researcher who worked on the study. “This study helped shed light on who is most impacted by food insecurity in St. Louis Park, and how the city can build on existing strengths and address service gaps to ensure all residents have adequate food.”

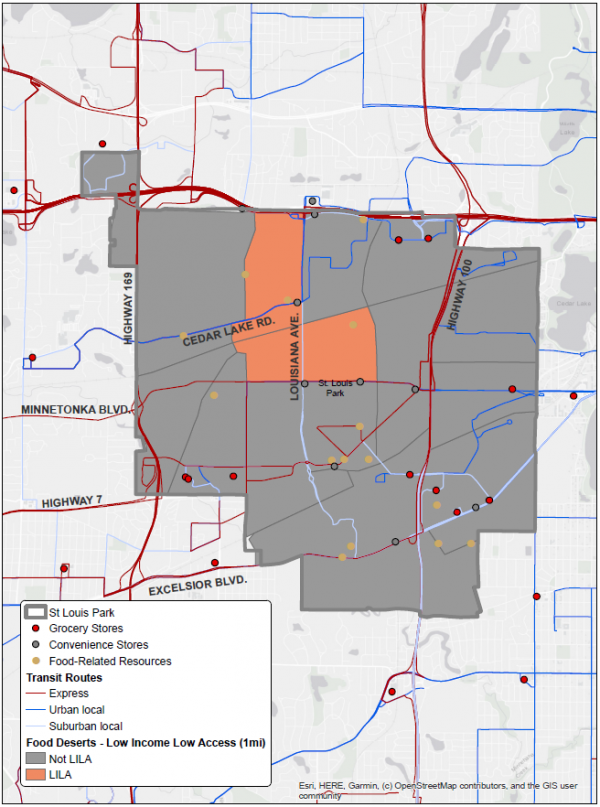

Food Deserts in St. Louis Park

St. Louis Park has two federally designated food deserts in the north central region of the city.

The USDA defines food deserts as low income census tracts (areas where the poverty rate is 20% or greater, or the median family income is less than 80% of the metro region) where at least 500 people or 33% of the population live more than one mile from a supermarket or grocery store. The food desert definition can highlight service gaps and is used by some federal programs when allocating resources or determining grant eligibility. It is important to note that not all residents in a designated food desert may experience difficulties accessing food, and some residents in other areas may face challenges with food access.

Resources Are Available to Support Food Security and Access, But Barriers Exist

The study found that St. Louis Park has a higher number of grocery stores per capita than surrounding communities, as well as convenience stores, food shelves, community gardens, and other programs that increase access to healthy foods. But the resources aren’t always known or accessible to all residents.

Other factors identified in the study that may contribute to food insecurity:

- Transportation: Eight percent of households in St. Louis Park do not own a vehicle. Study respondents said limited public transportation routes and schedules made it hard to get food, and walking long distances and getting to places in the winter, especially for adults with limited mobility, made it even harder.

- Housing costs: Over 25% of all households and 40% of renters in St. Louis Park are cost burdened, paying more than 30% of their household income in housing. When people have trouble affording housing payments, they have to make difficult decisions about how to prioritize their dollars, including going without food.

- Stigma: Study participants noted that a stigma associated with not having enough food can affect whether people seek help by going to food shelves or applying for SNAP, and may contribute to food insecurity being a “hidden” issue in St. Louis Park.

It [can feel like a] shameful thing for a parent to say, I can’t feed my kids. It [can feel] shameful [to] a senior to say, I’ve worked hard all my life and I’m looking fondly at canned food. It [can feel like a] shameful thing for a person just starting out [to say] I spent all this money for college, [but I] can’t even feed myself….It’s the myth of America that if you don’t make it big, it’s your fault. That’s part of it.

Raise Awareness And Collaborate to Reduce Food Insecurity

The study identified many ways the City of St. Louis Park could help reduce food

insecurity. Strategies included:

- Increasing awareness of available local food programs and services.

- Improving collaboration among schools, health care, nonprofits, businesses, faith-based organizations and community members.

- Establishing and supporting a cross-sector task force to identify priorities and strategies, increase community awareness, and guide actions.

“We learned a lot through this study, which took place before the pandemic,” said Meg J. McMonigal, principal planner with the City of St. Louis Park. “The world has changed dramatically since then and we know that the need is even greater. Our intent is to organize a task force with representatives from the community early next year to see what is being or can be addressed given the changing needs and environment.”

Top photo by Joel Muniz on Unsplash.